I have compiled following six books which combine fiction with some real life happenings. But the facts are unauthenticated and opinions are not very well considered and most of the content has been compiled from other sources. The books are stuffed with anecdotes that are hugely exaggerated and stories that are completely untrue.

1. Remembrance of My Indian Past

2. Venice of the Caribbean

3. Escape from the Acts of God

4. A Journey of Self-discovery

5. Next Life

6. My Former Life

7. Of Human Liberation

8. Laugh, Run, Leap, Sing for Joy, Anika

9. There is a Garden in Your Face, Priya

10. Blend in the Divine Glory, Arun

11. Reflect an Avatar in Your Face, Sanjana

12. Be a Meek Lover of the Good, Kiran

I shall be very happy to send any book free by E-mail to anyone who sends me a request. I also welcome any comments on this site.

My E-mail address: mmathur@tstt.net.tt

I have also compiled three serious books - The Neon Gita, Great Gurus and From Preposterously to Divinely. Last of these books can be seen at pustakpresspvt.yolasite.com

All the books contain passages that have contributed to my blundering along in spiritual progress and passages that have chronicled absurdities of life. During the coming months I shall endeavor to reproduce some of those those passages on this site.

I also contributed 11 articles on the Gita and 8 on Great Gurus to monthly online magzine Tattva. They are all are included in this site. Now Voice of India Feaures online Newsletter is continuing my series on Great Gurus. Thes aricles are uploaded on this site Great Gurus as and when they are published . Please feel free to give feedback

What follows are some passages from a few Chapters of 'Remembrance of My Indian past'.

Passages from Chapter II Studies at a Muslim University

That evening I asked Papa to suggest something to read which could be a good introduction to Hinduism without telling him the reason. He gave me a copy of the Bhagavadgita by C Rajagopalachari.

The very first chapter enlightened me on the nature of the soul. The soul is neither born, nor does it die, and goes from one body to another. As the one sun irradiates the whole earth so the soul irradiates the whole body.

At death, that is, when the soul departs from one body, it takes with it a load of character as developed by the activities so far gone through as a start for the next body. And the activities include thinking.

This world is pervaded by God in form unmanifest, the Gita went on; all beings abide in Him. But he stands apart and in His overseeing eye nature keeps the world rolling on.

Right action is to renounce selfish desire. Gyana (knowledge) manifests itself in the cultivation of a detached attitude in all work. Your duty is but to act, never to be concerned with results, while contemplating God. Action is better than non-action.

Self-control leads to true happiness, though in the beginning it is hard and bitter. After regular meditation a person welcomes clarity of spirit, the urge to activity, and even delusion as they come, but does not long for them again when they disappear. He remains the same in honour and calumny and same to friend and foe.

The Lord dwells in the heart of all beings, and through the forces of maya causes all beings to move like puppets on a revolving machine. None need despair on the ground that his sins have been too great or too many. Prayer and repentance purify the soul.

In whatsoever way man approaches God, even so does He bless them, for whatever the paths man takes in worship, they come unto Him.

It was past midnight by the time I read all this and my whole body was shivering with this extraordinary celestial knowledge. Knowledge, which I thought, was a great secret and had been trying to gather from the conversations my father had and which I could not put my hands on. Paradoxically, it was my father who provided that knowledge though he was quite oblivious of that fact. As next morning I had to get up early to cycle to the university I tried to snatch some sleep which came rather easily for I was floating in the sea of peace. But the call of the Gita woke me up at 3 a.m. and I went back to resume partaking of this new-found wealth.

Austerity in the spoken word constitutes speech that causes no annoyance and which is truthful, loving, and beneficial, and the study and recitation of the scriptures. Tranquillity of the mind, gentleness, reticence, self-control, purity of thought, these constitute austerities of the mind.

Put your trust in God and have no other thought; by his Grace you will attain supreme peace and the everlasting abode.

The performance of one’s own duty is worship of Him from whom have emanated all beings, and by whom all this is pervaded, and by such worship a man attains the goal.

For the first time in my life I felt at ease with myself. The secret of this world – and I had been all along sure that there was one – had at last been unraveled to me.

Passages from Chapter VII On the Road to Jhansi

Major General Wadalia won the hearts of all the officers and men when during the move he decided to march with the infantry for a couple of miles. The fact that his march saved no transport, caused more inconvenience all-round, and was meaningless, did not matter. I learnt how easy it is to fool hundreds and thousands of men by meaningless gestures.

And meaningless gestures were taking place at

all levels in the world at that time. Prince Aly Khan the greatest womaniser of

Europe and ex-husband of actress Rita Hayworth was appointed

American Secretary of State Foster Dulles put

together a curious entity he called the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation

(SEATO). Nehru refused to join it as he was against military alliances but made

a pact with

‘But Foster,’ Lippmann reminded him, ‘the Gurkhas aren’t Pakistanis they are Indians.’

Blind leading the blind – even Lippmann did not know that Gurkhas were not Indians either; they are Nepalese.

‘Well,’ responded Dulles, unperturbed by such nit-picking and irritated at the Indians for refusing to join his alliance, ‘they may not be Pakistanis, but they’re Muslims.’

‘No, I’m afraid they are not Muslims, either, they are Hindus.’

‘No matter,’ Dulles replied.

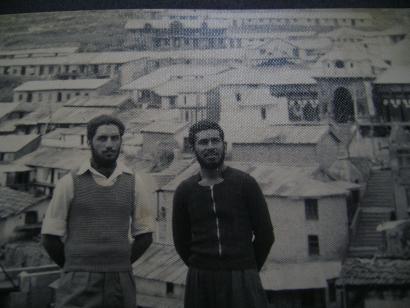

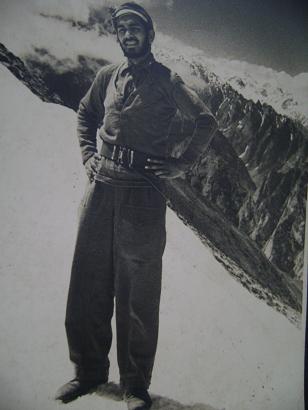

Passages from Chapter VIII At the Tibetan Border

The first day of

the serious recce was a gentle trek to the godly

Tapovan where there was a shrine for Shankaracharya, the eighth-century saint

who gave Hinduism back to

We merely removed all hair from our heads before proceeding further from Tapovan. The idea behind this was to save time while we were in the wilderness for the next three months.

A few days later, while sleeping peacefully at night at a campsite, the colonel woke us up all of a sudden at 2 a.m. and asked us, unreasonably we felt, to pack up then and there and move. It was a very quiet moonlit night and obedient to his orders we were marching within half an hour, though sad at the thought of leaving the campsite. Hardly had we been on the track for fifteen minutes that we heard a muffled explosion and a tearing sound. Rushing back towards the site we were dumbfounded to see tons of snow covering our campsite. An hour’s delay and all of us would have been buried alive in the avalanche which had crashed with such stupefying suddenness. From then on the colonel was our hero for stealing us away from death.

It was only a matter of time before we stared

at death face to face again. As we penetrated the upper reaches of the

Clutching stones and earth by both feet and both hands I crawled behind a more experienced guide. And seldom before or after have I repeated Lord Shiva’s name with more frequency and intensity. Even so, a big stone came rolling from the top, missed my head by a few inches and disappeared below the slide. Fear of dying filled my mind and I dipped in my pockets to munch almonds and await the worst. But just then the guide crossed over to the other side and shouted at me to keep moving. And from the back I heard words of encouragement from my colleagues. I drew a deep breath and decided to go down fighting. With nothing to lose now, surprisingly I crawled across the remaining landslide quite easily.

More from Chapter VIII

Winds at

The track to

On returning to Timmersain it was decided that

a smaller party would go for ten days to recce the

The

Still More from Chapter VIII

Most enchanting and exhilarating was my other

foray from Timmersain. Down alone, I went looking for the

A view of the

Not that what happened next day was any less

pleasant. For I decided to go over to Lakshmankund, or what has been renamed as

Hemkund by the Sikhs, a shrine about two miles away from the valley. On

reaching the lake I felt as if I had entered heaven. A lake of blue,

crystal-clear water was surrounded by seven snow-capped peaks. There was an old

temple where Lakshman had done tapasya (penance) during the Ramayana

period and where one Guru of the Sikhs had also come for the same purpose.

There is nothing for one to do there but instinctively pray to the Lord. No

wonder sages have always gone to the

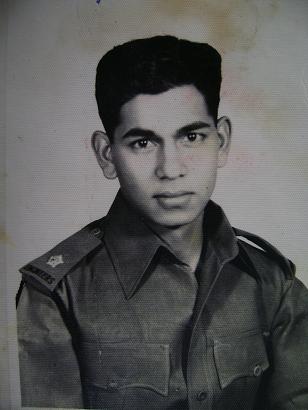

Passages from Chapter IX Birth of a New Life

It was certainly no trifling matter, at least to my instructors, when to relieve my boredom during the January–February 1958 bridging camp; I joined the Flying Club of Allahabad. At the rate of ten rupees per hour of flying time, my savings evaporated. It would have been worth it had I fulfilled my hopes of becoming a flying ace. Alas, I was quite inept at handling the Pushpaks, the training aircrafts of the club. My instructor, a Mr Verma, was himself so wearied of training a bungling trainee like me that just to get rid of me he asked me one morning to go ‘solo’ on the aircraft after making one circuit with me. My protestations that I did not feel confident were drowned in the engine noise and were finally shut out with the firm shutting of the co-pilot’s door from outside.

Accepting the inevitable, by my usual means of remembering Lord Shiva, and taking a deep breath, I taxied to the top of the airstrip. A green light from the control tower had me accelerating the throttle and then ever so gently pulling the control rod to make a clean take-off at the correct angle. After stabilizing the aircraft at the normal height I turned left and was soon in joyous amazement as I looked down and saw Verma watching the path of my flight. I savoured the rapture of my first solo flight.

At the correct spots I made two more left turns and then began to descend for the landing. Manipulating the throttle and the control stick expertly I brought the aircraft down to twenty-five feet from the ground to stall and land. Suddenly, I lost my confidence in landing the aircraft and, to avoid crashing, pulled up the stick and pushed up the throttle to go up in the air again. After two more abortive attempts it dawned upon me that sooner or later the gasoline would be exhausted and I would have to crash-land in any case. The sight of the flying club premises, where my instructor and other staff were clearly making my funeral arrangements, did nothing to lift my morale.

Determined to land, at last I came down, but

stalled the plane at twenty feet instead above ground instead of the mandatory

five or ten. I had the mortification of being watched by all as the little

aircraft fell to the ground, lift again in reaction, the cycle being repeated

three times before it finally came down on Mother Earth. In a hurry to get out

of the offending machine I accelerated and then ruddered towards the flying

club from the airstrip exit. But the acute turn sent the aircraft into a spin,

and the flying club members in despair. At length when flight weary me reached

the Flying Club area, the instructor and the workers advanced towards me as

behoved my sympathizers. But I was quite deflated when ignoring me they

directed their attention to the aircraft to detect any damage. No matter, I had

completed my ‘solo’ flight and eventually acquired a flying license. My

instructor celebrated the latter event by taking me on a daredevil flight whose

path traversed through two piers of a bridge on the

She was a majestic beauty who had dwelled in my imagination for a lifetime. I had only yearned for but had never really expected to see such a fairy princess in flesh. She was dressed in a gracefully wrapped sari, which followed her form exactly. She also appeared to be not a little frightened by a barking stray dog – the wretched dog should have been kissing her feet instead. I instantly chased away the swine who could not savour the sight of the greatest pearl in the world. Very gracefully she thanked me, and I felt as if I had rescued Draupadi from the clutches of Dushaasan!

Inside Mrs Hunt’s drawing room, after greetings and introductions, I sat opposite her. To my eyes she was the most adorable feminine thing I had seen in all my days. Indeed her effect on me was electric – thrilling – arousing in me a curiously stinging sense of what it was to want and not to have. Knowing that Zia was Muslim and not free, and I was engaged to be married, I agonised that I may never win her. It tortured and flustered me. Yet, so truly was I captivated that I desired to look only at her constantly. And then the revelation came to me that a beauty such as she transcends all man-made distinctions and conventions. And so she did.

As the evening progressed all invitees and hosts gave glimpses of their singing or piano-playing talents. Zia herself played a beautiful short piece Sugar in the morning, Sugar in the evening. To me this was the ultimate. When the time came for my performance, I lamented that I was yet to get my first lesson. But then the sweetest voice in the world articulated the most enchanting sermon of my life. ‘If you do not play for me Captain Mathur, I will never play for you.’ Just for her sake, how I wished I had the talent of Beethoven. That wish having been denied to me, I proceeded to play the piano with my eyes riveted on the music book in front of me and my right-hand forefinger pushing the piano keys as rapidly as possible till some genuine music lover brought the proceedings to a close by loud applause. Turning my eyes from the keys to her mischievously smiling face, I felt my soul passing into my heart and my heart into my eyes.

It was as if

I had captured loveliness in a work of art.

This work of

art was set down forever, so that to reminisce is always to have the same

precious sense of exaltation and adulation that has remained unabated for more

than four decades. What is worse – and I use the word with genuine regret – I

have not been able to fall in love with another woman since then. That evening

on returning to my Quarters at

More from Chapter XI

A host of

famous personalities were invited to mark the occasion of the 200th

anniversary of the Indian Institute of Science. Among them was the Duke of

Edinburgh, whose then marital life probably was a catalyst in his accepting the

invitation. The planned event brought the British deputy high commissioner in

If that was

the dream, then left out of the dream was the formidable figure of Mess

Havildar Sanjeev, who was present at all my meetings with the deputy high

commissioner, and who arranged meticulous cleaning of the mess, delicate

manicuring of the lawns, and tasteful decoration of all the rooms of the

building. Not to appear unemployed in the operations, I decided to spend my

time in the underground cellar of the mess where were stored numerous

invaluable silver acquisitions of the last 200 years. There I came across a

silver frame which held an autographed picture of a nineteenth-century Duke of

Edinburgh who was none other than a son of Queen

Passages from Chapter XII A Lesson from the Gita by Chinmayananda

’ What

follows is Sankara’s beautiful explanation of the seventy-first verse (Chapter 2).

That man of renunciation, who, entirely abandoning all desires, goes through life content with the bare necessities of life, who regards as not his, even those things which are needed for mere bodily existence, who is not vain of his knowledge, such a man of steady knowledge, who knows Brahman, attains peace (nirvana), the end of misery of mundane existence (samsara). In short he becomes Brahman.

To me now a plan for leading my life was beautifully chalked out: do your best in life, yet remain detached from the materialistic world, retaining love only for God. I thought there was nothing more to learn now. That would have been true had I retained the philosophy for all times. Alas, in many real-life situations I still came out a cropper; unable to resist the calamities that plagued my personal as well as professional life, I just suffered them alone – sometimes with great sorrow. But not for long. The moment I went back to the Gita, the clouds of doubt disappeared, and in due course of time better things descended over me – mainly at the plane where it mattered, my mind. I had always questioned the mandated daily scriptural study; now I know how essential this study is to prepare oneself for the vagaries of life.

Passages from Chapter XV - Oh Calcutta!

. There was

only one person in the world that was unpitiable – I. As usual, I turned to

philosophy for consolation. In the officers mess library I found an old book on

Spinoza’s writings which moulded my mind so much that I am compelled to quote

some passages from the book.

God is not a bearded patriarch sitting on a cloud and ruling the universe. God is not in any one place, but is everywhere according to his essence. God is cause of all events in the same way that the nature of a triangle is the cause of its properties and behaviour.

Men think themselves free because they are conscious of their volitions and desires, but are ignorant of the causes by which they are lead to wish and desire; it is as if a stone flung through space should think it is moving and falling of its own will.

There cannot be too much merriment… Nothing save gloomy… superstition prohibits laughter… To make use of things, and take delight in them as much as possible (not indeed to satiety, for that is not… delight), is the part of a wise man; to feed himself with moderate pleasant food and drink, and to take pleasures with perfumes, plants, dress, music, sports and theatres. A man with poor powers of perceptions and thought is especially subject to passion.

To use the imaginary rewards and punishments of a life after death as stimulus to morality is an encouragement to superstition and quite unworthy of a mature society. Virtue should be – and is – its own reward. Viewing the offender as the product of circumstances outreaching his control can cool anger at an insult; grief over passing of aged parents can be moderated by realising the naturalness of death. A strong man hates no one, is enraged with no one, envies no one, is indignant with no one, and is no wise-proud. Men under the guidance of reason desire nothing for themselves, which they do not also desire for the rest of mankind.

The prophets excelled not in learning but in intensity of imagination, enthusiasm, and feeling; they were great poets and orators. They may have been divinely inspired, but if so it was a process that Spinoza was unable to understand. Perhaps they dreamed they saw God; and they may have believed in the reality of their dream. We may be absolutely certain that every event which is truly described in the Scriptures necessarily happened – like everything else according to natural law; and if anything is there sat down which can be proved in set terms to contravene the order of nature, or not to be deductible there from, we must believe it to have been foisted into the sacred writings by irreligious hands; for whatsoever is contrary to nature is contrary to reason, and whatsoever is contrary to reason is absurd. The idea that Moses, Jesus and Mohammed were frauds and fakers was soon to be known as l’esprit de M Spinoza.

Of all the things that are beyond my power, I value nothing more highly than to be allowed the honour of entering into bonds of friendship with people who sincerely love truth. For, of things beyond our power, I believe there is nothing in the world, which we can love with tranquillity except such men.

One such man now entered my life. Eddy Banaji

was a fellow engineer captain who held some obscure appointment in an obscure

organisation called Embarkation Headquarters. He was also stuck with a bullying

boss which was a satisfactory bond between him and me to commence a fair friendship. Both of us would spend

long hours at work without achieving very much and periodically suffer verbal

lashings from our respective bosses. It was only in the late evenings that we

would sit down in the verandah of the mess (which used to be the residence of

Lord Kitchener in the days of yore) after dinner and chat away about the

futility of life in general and the army in particular, our loves, and our

future. Eddy was a very self-effacing Parsi, who avoided other Parsis and was

perhaps the last sincere friend that I was to encounter in my life; so attuned

to my feelings was he that it appeared he had grown to be a twin of mine.

A third person to join our group was a gunner,

Andy Coutts, who, to our utter delight, cared less for philosophy and more for

the sensual pleasures of the world. He spurred the three of us to outings to

places like Great Eastern Hotel to view striptease shows, art joints near