MORE PASSAGES FROM 'REMEMBRANCE OF MY INDIAN PAST'

Passages from Chapter XVII Climbing the Heights of Kedarnath

With a view to reaching the hills at the earliest, I caught a bus for

Rishikesh without wasting any time in Haridwar yesterday morning. My first

destination was ‘Muni-ki-Reti’, a religious camp set-up by Swami Shivanand, two

miles from Rishikesh. I had heard a lot about the swami and I wanted to meet

him. At 9 a.m. he came out to his office, followed and helped by a long train

of disciples. I was surprised to find a number of foreigners, girls in

mustard-coloured saris and boys in just underwear and angarchhas. These

people were behaving like orthodox Hindus.

The swami is seventy-four years old and is said to be already beyond this world. But to me he gave an impression of being very much self-centred. First he looked at a number of his photographs with visitors. Then started the ceremony of washing his feet by milk water. Mantras were recited simultaneously. Later, the charnamrat was distributed to all present. And everybody, including the foreigners drank this with great respect. Somehow, I was left completely unimpressed by the whole proceedings.

Swamiji then went out and posed for two pictures with his new foreign disciples. Another ceremony was performed and some prasad distributed. Now the swamiji entered another room by the side of his office where a comfortable chair with thick cushions was laid out for him. A number of books containing his writings were kept by his side. A Telegu lady recited some Sanskrit hymns in which everybody joined. The recitation ended with an English prayer for self-purification.

Swamiji first

noticed me when I went to him to receive flowers, which he was distributing to

everybody. ‘Have you come from

After he had distributed his books to the followers present, I approached him. His face bore the sign of a question mark. I hesitated. ‘What do you want?’ he asked firmly. ‘I have a confused mind and came to seek your blessings,’ I mumbled. ‘Do japa and read this book and everything will be all right,’ he commanded after handing over his book Amrita Gita to me. ‘But I can’t concentrate even for a minute,’ I argued, ‘and my mind is ever wandering.’ ‘The vain wandering of several births have left this impression. It will take sometime before you get over it. Do japa,’ was his final reply. I went back to my seat and he started signing outgoing letters. When he showed his palm to a palmist called Ghosh to find out what was in store for him in future, I wondered if anybody, whether a saint or a prophet, ever gets rid of his ego even if he finds God. I tried to do some japa silently. As if to test me at this stage appeared a lovely, unassuming, ever smiling, pretty European girl dressed in a saffron sari which hid a most seductive figure. I looked at her, looked at swamiji, looked inside my heart, and thought of God and His creation.

‘Have you done japa

before?’ Swamiji asked me all of a sudden. I looked blank. A Madrasi monk

sitting next to me prompted me to go to him again and ask to be initiated.

‘What mantra do you want?’ ‘

‘How long can one stay in the ashram?’ I asked one of swamiji’s ardent disciples. ‘As long as one wishes,’ he replied. ‘What does one do to earn his living here?’ I questioned. ‘Good qualities and a spirit of service is all that is required here.’ ‘It will be my endeavour to develop these qualities and remain in the world,’ I said to myself. ‘If only I fail there will I come up here.’

More from Chapter XVII Climbing Heights of KedarnathFollowing the example of my fellow traveller, I mustered up enough courage to go down the ghat of Alaknanda and have a dip in the freezing water out in the open. I was still recovering from the not-so-pleasant effects of the holy bath when I was handed over to a panda. This panda really treated me like an inanimate substance. Sometimes he would clutch my hand and pull me around, then he would push me and guide me to a particular spot, then he would take charge of my hands and make me do things which I understood not at all; but the climax came when he got hold of my head and literally rubbed my forehead on a statue. All this time he had been zealously reciting some Sanskrit hymns. Little did he realise that his poor victim couldn’t even concentrate on God under those circumstances because he always wondered what was coming next! Personally speaking I liked it much better last night when I was left alone to do what I wished.

Coming out of the river I saw the most beautiful sight. Behind the temple was a snow-clad mountain turned golden due to the rising sun’s refreshing rays and contrasting with it was the background of a sky blue sky! Once again I missed taking photographs of such a rare scene; I thought I would take the pictures after finishing all the ceremonies; but by the time I was ready with my camera thick clouds veiled the sun. As a result I spent a few moments to put away in my memory, the scene which would keep bringing moments of joy anywhere, any time just by being recalled from memory.

The last item on the agenda was paying respects to a ninety-year-old yogi who lives all the year around at this snowbound location. During winter, when everything is covered by snow, he confines himself to his small hut. He has reduced his necessities and interests in life to get divine pleasure.

Why can’t others even attempt to deny some luxuries of life? Why can’t I? I don’t think a human being can achieve this in a short time. One has to regulate oneself for years, nay even several births, to reach that stage. Nevertheless the important thing is to make an endeavour to do right.

I was lucky to be alone with him and had some enlightening conversations. He definitely clarified one doubt of mine. For that alone it was worth coming all this distance. On my asking him if my marriage with Usham would be the right thing to do, he simply replied, ‘The question of right or wrong does not arise, you have wanted it so much that nobody can stop it.’

Going back to my room I wrote a few letters and then came out to wander around and take some photographs. But the snow-clad mountain was still shrouded with the thick white clouds. Lucky are those who get some opportunities to do what they want. But most of us are stupid and are unprepared to grab the opportunity when it comes and later we lament our unlucky stars. I once again make a promise to strive to remain prepared for opportunities in future. There was nobody to chastise me about this mistake. But then it is enough that the cloud of incompetence demeans oneself before one’s own eyes.

Even so, I reconnoitred the area. Went up to the Bhairava temple about half a mile up, took some photographs and then I let my mind and heart be absorbed in the colourful flowers. I could see millions of red poppies and buttercups. I plucked one specimen of each for you. They looked so beautiful, as I made a small bouquet of them. I wished I could hand them over to you by some divine means.

Passages from Chapter XVIII Honeymoon at Darjeeling

After spending a couple of days at

The very first evening Usham captivated the

brigadier. Looking at his own whisky-loving plain wife, he could not help

asking Usham what she saw in me to marry me. I resented the question, but the

awkward fact was that even I did not know the answer. With bated breath I

looked at her. ‘He is brave,’ came the unexpected reply. Now Brigadier Gyan

Singh was interested in Brigadier Gyan Singh. Quite simply and directly. And in

a way that I thought him to be a genius. ‘Why do you say that? Did he fight in

the Burma Campaign under Field Marshal Slim? Or did he lead the first Indian

expedition to

Passages from Chapter XX A Son is Born

To make our lives

a little more exciting a letter came from Jussawala, Zia’s lawyer in

Portents were not bright from the beginning. I

bought our own air tickets from

A wiser man now, the trip to

A bigger gain of

the

Excursions

were organised for us to visit the sights in and around

More from Chapter XX A Son is Born

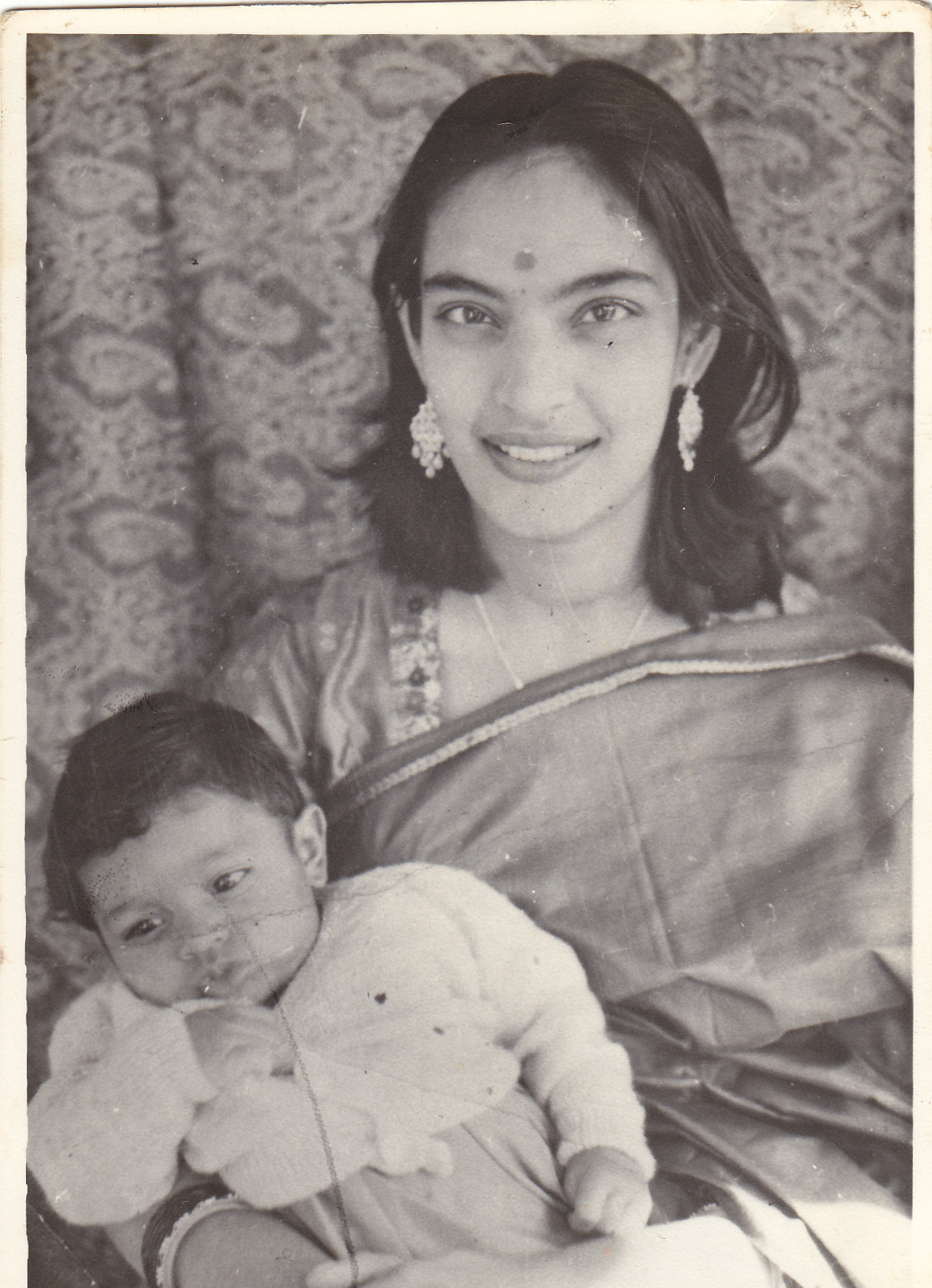

It was raining intensely on the afternoon of 6

September 1961 when the baby was born. From the

What should

have been a great time for both of us, watching our precious child grow, was

turning sour, thanks to Usham’s mother. She kept telling her daughter that she

was living in terrible conditions after childbirth and that she should not get

up from the bed for forty days. As a result, after the maid finished her duties

in the evening, I had to remain awake during the nights to take care of the

mother and the child. Fortunately, Usham’s grandmother always restrained her

daughter from damaging our marriage.

In fact, the old lady was quite an institution

by herself. And it was to her that we looked for guidance. She went and called

on Ms Padmaja Naidu, then governor of

With the eventual departure of Usham’s mother

from

Baooa gave us the pleasure of coming to us to

take care of Usham and the baby for a few weeks. I really haven’t met anybody else in

my life that is satisfied with so little, is completely non-demanding, is

always ready to help others, and is thrilled by small pleasures. She loved

living at our

Varun was dark like me, handsome like his

mother, and tall for his age. Usham’s thoughts centred on him as long as she

was awake. I started planning his welfare and for the first time started saving

money for him. Varun was the pivot of the

house; every desire ended somewhere in him. Usham and I had ceased to be

self-justifying beings; we never thought of

ourselves save as the parents of Varun. Perhaps he knew all about his

importance. Even when he was punished – which was quite often – he was made to

understand that it was because much was expected from him.

From Chapter XXII Which Major?

In the hope of giving my wife a pleasant

surprise, on the day when I got my promotion and posting order, I withheld this

piece of intelligence from her. In any case, she was ignorant about military

promotions and appointments and the situation did not interest her. I, on the

other hand, decided to make the best of my remaining few weeks’ stay in

But at the end of these trips she was quite tired of eating out at godforsaken places, could not bear the cooking of someone who could not and would not hear her advice on finer points of the culinary art, and she herself did not have the time nor the inclination to cook in addition to looking after Varun.

The problem of sustenance was solved by eating in the nearby officer’s mess where a few bachelors would join us in the evenings for drinks before dinner. Most of them were junior to me; even those who had picked up the rank of major a little earlier had done so due to expansion of their regiments. But she rather enjoyed the respect and attention accorded to her by these majors, who were in turn treated with deference by the lieutenants and captains as required by military etiquette. The situation did not peeve me because I knew that Brigadier Shivdayal Singh was about to rectify the matter.

Soon enough

a signal came to my desk at the office requiring me to assume the post of

garrison engineer, Shillong, in the rank of major. It was undeniable that I was

a lucky mediocrity at whom this attractive post had flung itself. In all

modesty I immediately rang up my lovely wife – me and my sense of humour – and

asked how she would like to be the wife of a major? A short pause, and then she

inquired, ‘Which major?’

At the office I summoned a conference of all contractors and engineers only to find that most of the projects were on hold because of lack of decisions. I simply asked for suggestions from them and then decided on the most sensible solution even if it happened to violate some regulation or appeared to bestow extra benefits to certain contractors. I would visit the sites every day mainly to educate myself but in the process site workers also got decisions on the spot. Within a few weeks the engineers and contractors had started achieving a lot. A couple of bridges that were held up for months showed remarkable progress, trucks and jeeps that were off-road for want of spare parts and were in the process of being condemned were put back on road, buildings of the corps headquarters were being repaired, new quarters for married personnel were being built, and above all the corps commander’s residence was being refurbished in accordance with the wishes of Mrs Umrao Singh, her daughter, and her husband. Evidently she was a proud, even a haughty creature, with her careful controlled politeness. She considered herself to be superior to all men in uniform in Shillong. She certainly displayed no great respect for the general; maybe the rumours then abounding about him, similar to those which made American President Clinton immortal thirty-seven years later, had something to do with that attitude.

Through no fault of mine, I found myself in an unaccustomed situation. The station was abuzz with the turnaround of the division when Colonel and Mrs Kale returned to the station. He was a tall, kindly, polite and warm Maratha and she was a short, shapely, flirtatious and voluptuous Punjabi. They both said that everybody was talking about how Major Mathur has changed the division for the better. I could not help stealing a look at the sky and wondering at the irony of life. When I did my best, I was adjudged a failure; and when I was clueless and let others work, I was successful! From day one we hit it off in style and formed a mutual admiration society. If I had any problem at work I just had to give him a ring and he would be there to help me. But my newly acquired reputation also condemned me to longer hours of work. In one breath I would say all leisure was rot and it was only work which mattered. And in the next I would suddenly demand how was it that I had no time for anything but work, unlike some officers of corps headquarters. However, I was plagued by apprehensions about the management of the division.

Fortunately, my will power to continue to see

improvements in the division remained a driving force. But my capability to

convert this into action was being impaired due to commencement of special

police inquiries against engineer Dutta and adverse confidential reports by the

CWE on the other two engineers. I assured the police that Dutta was an honest

man and the CWE that the two engineers had become angels overnight. And with

that, all my junior engineers acquired, in an increasing degree, the supreme gift of

unquestioning obedience to me!

More from Chapter XXIII - Uaccustomed acclades at Shillong 1962

At about that time two well-known

personalities of Indian politics passed away. One was the octogenarian chief

minister of Bengal, Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, who had ruled

Swami Ranganathananda of Ramakrishna Mission visited Shillong and was invited to give a talk at the officers’ mess to a small gathering. He told us that the Upanishads present religion as a matter of experience of the highest truth, and not as mere belief. This is the supreme characteristic of the Sanatana Dharma. Vedanta teaches the scientific-philosophical approach to the highest reality. The Vedanta allows and welcomes questioning by seekers. No dogmas can allow or stand questioning. Truth alone can do it. The Vedas say:

This Atman (being) hidden in all beings, is not manifest (to all). But it can be realised by all who are accustomed to inquire into subtle truths by means of their sharp and subtle reason.

Something stirred inside me, touched me, and I had a feeling that all was not lost. Somewhere there was such a thing as peace of mind and goodness. That night when I dozed off, thoughts of the mystery of life merged into the incoherence of my dreams.

For a while social life took centre stage at

Shillong as there was talk of the impending move of the corps headquarters to Siliguri. The governor of

In due course of time IV Corps HQ arrived at Gauhati after evacuating from Tezpur. And I as the GE had to provide accommodation for them.

All army wives and children were asked to

leave

Chapter XXVI The Life Cycle

My mother was a perfect karmyogi,

certainly none greater have I come across in my long life. Every morning she

would get up at 4 a.m., have a cold bath, say her prayers, read the Ramayana,

and then straight on wade into the housework of cooking breakfast for the whole

family, supervising the cleaning, ensuring everybody had lunch and dinner at

their respective preferred timings, and making sure that the laundry was taken

care of. Only in her rare spare time would she amuse herself with reading

novels, listening to music, going to movies, or socialise with her women

friends – Papa spent

every evening at the Library Club where he went to play bridge. She virtually

sacrificed herself for the welfare of the family.

Nobility,

sweetness, cheerfulness, charm and friendliness always

oozed out of her, and

divinely free of indolence she was when it came to any errands to make any

member of her family more comfortable. She always ate last and retired for the

night after everyone else was in bed. The only desire that she ever gave

expression to was to pass away from this world while still working, and without

troubling anybody for even a glass of water. Rather than suffer any disabling

sickness, she had the sweet urge to close her eyes and surrender utterly to the

perfect safety of leaving the body. With an instinct endowed to her by her

daily meditation, she felt the vastness of the divine embrace enfolding her

liberated spirit – Brahma engulfing the soul, the only real part of her

temporary personality.

I recalled that it was only two days back that I had received a letter from her in which she revealed how happy she was to read adulating sentiments in my last letter which I had fortuitously recorded. She had also declared that she would journey to Gauhati on the day I chose for helping in Usham’s childbirth. Might it be that her liberated soul had entered Usham’s womb?

Next morning in the Indian Airlines planes to

Nor I, nor

thou, nor anyone of these,

Ever was not, nor ever will not be,

Forever and forever afterwards.

All, that doth live, lives always! To man’s frame

As there come infancy and youth and age,

So come there raising-ups and laying-down

Of other and other life-abodes,

Which the wise know, and fear not. This that irks –

Thy sense life, thrilling to the elements –

Bringing thee heat and cold, sorrows and joys,

’tis brief and mutable! Bear with it, Prince!

They all joined the funeral procession from

home to Chandaniya, the cremation ground. Relatives, friends, neighbours, and

numerous others whose hearts she had touched during her life – they all filed in. It was for the

first time that I witnessed a cremation. The body was rested on a pyre of

firewood, ceremonies conducted by the family priest, and the pyre lit by Papa.

It was remarked, that a lucky woman was she for having passed away while her

husband was alive, the children grown up and educated. And she went away

painlessly. All that was true. But she did not want to die that soon. I knew

she wanted to come to Gauhati and be there for the birth of our next child. I

thought of her age; she was only fifty-three.

I thought of her goodness; she was ever ready to do a good deed, and never a malicious thought entered her mind. I thought of her charm and friendliness; she was permeating them all the time. Although always she had done her duty, I knew she had thought much more. I wondered if she thought of the adventure of breaking away from it all. I did not want to leave the scene of her final departure before the cremation was complete but in a gesture of mercy to the gathered barbarians, the priest suggested we all leave. I had a last look at the sight of the universal unknown engulfing the minuscule unknown that had been the part of her temporary personality.

27 January

1964 was a Sunday and a number of people visited us that day mainly to inquire

about Usham’s health. They all came and socially chatted with us, men drinking

beer and their wives displaying themselves as fair statues. It was only when

Mrs Nayar came at about 4 p.m. and saw Usham that I was chastised for keeping

Usham at home in what she said was the eleventh hour of pregnancy. Straightaway

I put her in my car, and with Mrs Nayar in attendance, drove to

So far all

the women that I had met were like books that I had already read. But this young

lady was a library of the unknown. Never one blind to beauties, my affection

for her could straightaway make out that she was going to make our lives the

sort of which dreams are made. Next morning I took two-year-old Varun to see

his new sister. The new sister was at that time being nursed by her mummy and a

great sense of delight spread over Varun’s face on seeing her. Spontaneously he

roared, ‘Dolly, dolly.’ And Dolly we have called her since then.

28 January

was celebrated by the Corps of Engineers as the day when the first Indian

engineer-in-chief, Major General Asarappa was commissioned, and who on

retirement from the Indian army promptly got employment in the British army in

the rank of major. Normally these dinners were stiff, black tie, boring, formal

affairs. But that year I lost all inhibitions and used the occasion to

celebrate the birth of my baby daughter – even old Colonel Nayar was roped in.

I think all of them were quite happy to divert from the irrelevance of the day.

Obsessed with making our newborn immune to all possible diseases we got her inoculated and vaccinated against whatever the doctors advised. In the process poor Dolly suffered quite a bit, especially when one vaccination itself became septic, and left a permanent mark on her. Even so, because of her I was now free from the pain inflicted by Colonel Nayar and revelled in living. I can perhaps very truly say that from then on I didn’t decently envy any other human being, rich or famous, and have been content with my mediocre career.

Chapter XXX What did you do in the War, Daddy?6 September

In the afternoon went with DQ (for deputy assistant quartermaster – administrative staff officer) of the brigade to select a brigade maintenance area. En route two Pakistani F 86 planes flew over us for reconnaissance and we found cover under a tree. When we returned, the deafening noise of enemy shelling of our positions greeted us. Our own artillery regiment (from TA – Territorial Army) was without ammunition and as such could not return fire and was withdrawn from forward positions. I was given the task of protecting left of the Sulaimanke – Fazilka road. I redeployed the field platoon, organised the defence, and even planned a counterattack. But let me confess that when I tried to steal some sleep I didn’t feel very comfortable. I hate war.

Life is strange. A guy dreams of war all his life, joins the army at the first possible opportunity, trains for it for twelve years, and then on the first day he hears shelling in anger – he hates war. Still I had the good sense of not disclosing outwardly what I felt inwardly. It was of paramount importance to maintain an outward appearance that radiated enthusiasm and confidence. At least my laborious study of military history was paying off even as my study of philosophy revolted against war.

11 September

On 7 morning C Platoon was sent up but it couldn’t start working on

minefields for 14

After the brigade

commanders’ conference at 1700 hours I took NP, C Platoon commander, to 14

I left a blank page after that entry hoping to describe the dramatic event of the remaining evening at leisure. Apparently that leisure I did not find till today. But those hours are so deeply engraved in my memory that even after more than thirty-four years I can narrate events of those hours as if it happened only yesterday.

That was the first time I watched a night attack by the enemy. As the enemy troops advanced towards our position their artillery fire was lifted and Verey Lights went up to illuminate our areas for their troops to attack our positions. Simultaneously, our own artillery, mortar, tank, and machine gun fire intensified at the advancing enemy. Soon the advancing enemy troops were exposed to the sights of our infantrymen by the illumination of our own Verey Lights. Concentrated heavy small arms fire struck the enemy with great force. Screams and groans filled the atmosphere and then suddenly there was silence. That signalled to us that the enemy attack had been beaten back. First I thought of heading back to my own unit lines on foot; that seemed to be the way not to expose myself anymore to Pakistani hostility. Then it occurred to me that my jeep might still be in the area where I left it with the driver Govindaswami, still waiting for me – alive or dead. So thither I stumbled to. Alas, in vain. There were no signs of either the jeep or its driver.

Assuming that the enemy had captured them, I started my long walk back to the unit area, which was about six miles back. The night was completely dark, the sky was completely cloudless, and the atmosphere completely soundless. Apparently that night God had withheld permission for the tree leaves to oscillate. Even the delicate foliage of a clump of pepper trees did not stir. Breathless was the darkness cooled by the early autumn. My mind had difficulty even in visualising Usham, Varun, and Dolly as even my soul appeared to have left the body. Mechanically reciting Hanuman Chalisa I let my legs do the walking under the almost continuous canopy of the trees lining the road – all the time looking out for enemy infiltrators. Up to that day I had an idea that God is very far away and is very high above. Not any longer. I felt He was with me. After a thousand years (so it seemed to me then) the unit sentry’s pale face gazed at me having heard the sound of my hasty and ponderous footsteps.

Well might the sentry imagine that he was seeing a ghost. For my driver, having witnessed my running and falling at the commencement of the battle, waited for another ten minutes for any signs of life in me, and then rushed back to the unit to take the tidings of my being killed in action! The fact that the news was slightly exaggerated was celebrated on my return with mugs of rum in my bunker with other officers. I savoured the moment of relief from the greatest danger that I had ever faced from the enemy.

From Chapter XXXII CHEATING DEATH AT HUSSAINIWALA

20 September 1965

At 4 a.m. I was woken up in my bunker by a ring from the brigade major who wanted to see me immediately. At his office I was apprised that the situation was forbidding, with 2 Marathas out of communications, presumably overrun by the Pakistanis. The brigade commander was ordered by the corps commander to move to Hussainiwala immediately with two troops of tanks, one artillery battery, one field platoon, and the officer commanding 10 Field Company. However, before we left at 6 a.m. the good news came that 2 Marathas had repulsed the enemy attack. We reached Hussainiwala at 8 a.m. and met a confident Colonel Nolan who told us what he needed to bolster his defences. I quickly worked out the requirement of mines and defence stores, and rang up the brigade major to send them up.

I was very glad to find that three enemy tanks had been disabled by the anti-tank mines laid by us, due to which the enemy assault was beaten back.

Soon I organised a recce party for bridge demolition, another for minelaying, and earmarked yet another for the demolition of the three tanks. But the last task did not have to be carried out as the tanks were subsequently destroyed by the recoilless guns. I left Colonel Nolan at 1700 hours to report to the brigade commander who advised me to see him again next morning regarding the demolition of the bridge.

Amid falling shells, I slept in a pukka building for the first time since the operations commenced.

This is the sort of stuff soldiers do. There

is neither virtue nor sin in it. It is all part of the same thing. But what

Pakistanis were trying to do was not nice. Nonetheless, I had one of my better

days of the war that day; what with three enemy tanks destroyed by our mines

and I helping the brigade and battalion commanders in defence. When I took off

my helmet for a short while at his bunker, Colonel Nolan shouted and asked me

to put it back on my head. Immediately after, he asked me to take no offence. I

told him I was taking no offence except if

shrapnel hit my head!

It must be said that engaging together in the war effort made us all feel like part of one big soul. That night I slept well even though the shelling was going on around me. The fear of war had been driven out by constructive work. That internal calm was better than many joys that I have known in my life.

From Chapter XXXIII Ceasefire and the AftermathThus my life changed

overnight – changed as only a sudden stoppage of firing in a battlefield,

without any defeat or victory can change. Just a day earlier cooked food, a

glass of water, or even going to bathroom seemed luxury. Today we drove around

in safety and watched the destruction of villages, vehicles, tanks and humans.

And everywhere, weary people were stretching. How this seemingly unnecessary

war had, and continued, to mess with thousands of lives which were forced into

this ugly situation. Yet they say every man is born free.

The well-armed

hordes of Pakistani cavalry attempted to drive towards

Even so, listening and watching the stories of the enemy forces made me wonder why these people think they are so different from us. Driving around in the wilderness even my soul did not appear to be mine but rather like a part of a great big soul which has to be with the rest. And what was being achieved by freeing prematurely so many souls from their bodies? Some of their bodies were still lying around – a ghastly sight, confirming my view that human beings are just like any other species, in that they are born and then they die. It is purely our egoism that makes us think we are superior.

From Chapter XXXV Defence Services Staff College, Wellington 1965/66My old hero from the armoured division days,

George Narayanan, now a colonel, turned up for a few days to visit his

brother-in-law, Charlie Murty, at

At the end of the training season Indu, wife of my friend Ramesh, who was DQ of the Division, was entrusted with the task of staging an English play for the Army Club, the hero of which Johur aspired to be in order to fulfil his ambition of excelling as an actor. He approached Indu for the role and when told that she would think about it, he boasted to one and all that he had been selected for the role. When finally Indu did choose her man, she had the task of making the blow light for Johur. Apparently she told Johur in Hindi that he was not selected for the role because of his height. The equivalent Hindi word for height actually means length. And ‘length’ is the word Johur used when telling us why he could not fit the role in the play. ‘It was because of my length,’ he explained in English.

Usham had no such problem in explaining her

predicament on the morning of 16 May when she rang me from her hospital bed at

the Military Hospital, where she had been admitted a day before. ‘I am dying,’

she declared. Panic-stricken I rushed to the hospital to find a comparatively

calm Usham complaining of excruciating pains, which, presently led to the birth

of a beautiful baby who was instantly exclaimed ‘Fairy’. Next week I received

orders to move to Rangiya in

From Chapter XXXVII - Ascent to Regimental Command

I took the regiment out to a bridging camp for six weeks to a nearby river and let them train extensively in building bridges and rafts. The grand finale was a demonstration of the regiment’s prowess to which all the brigade commanders of the division and the GOC himself were invented. The GOC reckoned this to be an opportunity to impress his corps commander, Lieutenant General ‘Happy’ Khanna (commanding IV Corps) and requested him to witness the ‘attitude of aggressiveness’ of his division. Since both the corps and the divisional commanders were from the artillery, I decided to add icing on the cake by demonstrating ferrying of mortars and medium machine guns on mules swimming across a water gap.

On the appointed day, the day on which I expected to win glory, I prepared a speech of which Guderian and Slim would have been proud, and delivered it fluently to the assembled generals and brigadiers. The atmosphere was charged with great expectations. Like clockwork my sappers built various bridges and rafts over which troops and equipment were moved. Finally I gave the signal for the mules, on which were tied guns and mortars, to be launched in the river. First three mules swam majestically, the audience broke into applause, and a sense of pride pervaded me and my men. Alas, the fourth mule lost its confidence midstream, made manoeuvres to return to the home bank, and in the presence of the august audience drowned in the river unceremoniously. I stopped further launching of the mules and sent a few good swimmers to untie the gun from the drowned mule, and retrieve it from the shallow and slow-flowing river.

But the damage had been done. The two generals walked over to the riverbank where the other loaded and now reluctant mules were waiting, and gave me a tongue-lashing of my life. I ask the reader to forgive the confusion which pervaded my mind at that time. I looked at the generals and looked at the mules, then I looked at the mules and looked at the generals, I again looked at the generals and looked at the mules. But in my confusion I still could not be sure which were the generals and which were the mules.

I presented no such confusion in my GOC’s

mind, though. He gave me an assignment to personally carry out a reconnaissance

in

And perish I almost did when crawling on a precipice I slipped down towards the ravine a thousand meters below. The slope was sandy and I could find neither bush nor stone to hold on to with my hands. Slowly but surely and helplessly I kept slipping down and was even afraid to shout for help lest the shout accelerated the slide. Silently I uttered my last prayers and calmly awaited the worst. Fortunately, Paul was not very far behind, and came to my help. He lay down flat on the ground and extended his hand which I grasped, to regain solid ground – and my life. Without any fanfare, after a ten-minute break we continued with our mission. On return I spent hours preparing a report on my mission and when I handed it over to the general I knew I had won him back for he gave me a smile which he normally reserved for the occasions when I had handed him an unmakable bridge contract.